The Pursuit of Passion: A Rational Way of Following Your Dreams

Do what you love, but make sure you’re good at it

by Harrison Yu

We have all heard a variation of the adage, “do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.” And then you might ask yourself, “what am I passionate about? Once I find that, I’m set.” I think this—without skill or a plan—is dangerous advice that society romanticizes.

Passion for your work is something that genuinely sparks curiosity and desire to constantly improve. Passion may seem elusive and unattainable, but I do believe that that it is possible to follow your passions, with just a simple guiding rational framework.

Following the emotional pursuit of passion requires a rational framework in order to succeed — which I argue is the only way to build a career. First, homing in on a passion that can be translated into a profession, is the foundation of this journey. Next, self-critical reflection of competency and motivation is crucial to making a passion a realistic pursuit. Finally, planning a roadmap that will allow you to activate your skills within your passion will enable the fullest pursuit of your passion. If you are going to spend over 70% of your waking time doing something, you better do something that you love, something that you are good at, and something that you have planned a viable path to ensuring you are the main character in your own story—in short, following your passion.

What do you love?

Concept One: always follow your passion. Most of us are trained in the very Postwar Americana sense that if you work harder than anyone else, you can achieve anything. This only works up to a certain point. Yes, you need to work hard to do well in life, but at a certain point, sheer hard work without a more intrinsic motivation limits your ability to be the best you can be.

If you are doing a job solely for external approval or for money, you will burn out (hence the classic midlife crisis) and never do as well as the person who actually loves the job for what it is. People who are passionate about their jobs approach problems in creative ways that unlock new perspectives and are constantly learning.

A few foundational questions you can ask yourself as a litmus test to see if you are actually passionate about something:

Are you improving and learning each day or are you humming at the status quo?

If basic life necessities were taken care of, would this be the thing that you choose to do?

Would you be telling the truth to your 10-year-old self that you are doing what you love?

Perhaps specific industries are not interesting to you, but rather, you are interested in a broader function. For example: do you like creating the big picture idea for other specialists to execute? Maybe product marketing & strategy is your calling. Do you like negotiating deals and strategizing based on the numbers? Maybe business development is your calling.

Whether it be industry or function, determining what you are passionate about is critical to then seeing if you have the skills to support your passion.

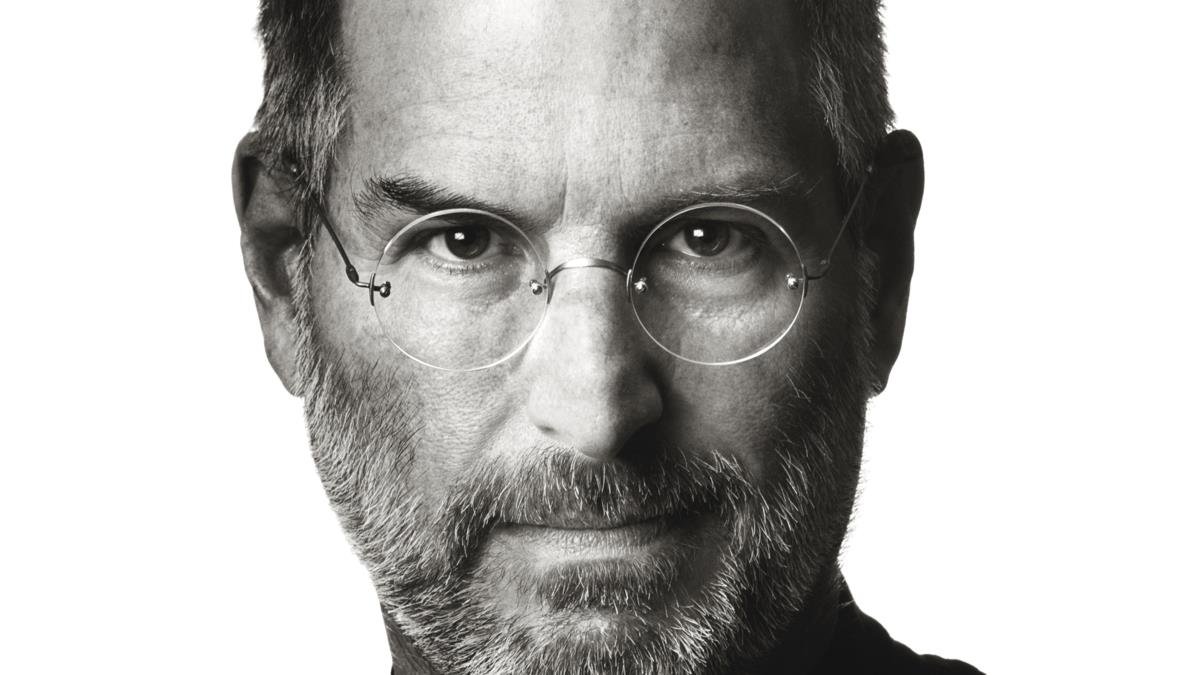

“Being the richest man in the cemetery doesn't matter to me... Going to bed at night saying we've done something wonderful... that's what matters to me.”

—Steve Jobs

Are you actually good at it?

Concept Two: have the honesty to ask if you have the skills to do well in your selected passion. It is not necessary to be a child prodigy, but a basic talent in your selected passion is a necessary starting point. The next step is to apply the mentality of Malcom Gladwell’s “The 10,000 Hour Rule” to obsessively practice your craft to become the best that you could possibly be.

Pause.

If you are not willing to put in the work to get even better at your passion or if you do not think with even all of that practice, you will not be in the top 10% of that field, you did not follow Concept One. It may be advised to relegate this to a hobby instead of a career. Repeat this self-reflection until you arrive at a passion that you can spend 10,000 hours living and breathing.

Ken Jeong is a trained doctor, but it turned out is an even better comedian. Phil Knight is a trained accountant, but it turned out is an even better visionary of athletic shoes. These two people easily spent thousands of hours on their original vocations and could have gone through their careers that they were told to pursue. Instead, they identified and followed their passions that they were really really good at to build overwhelmingly successful careers in their respective fields.

Another core concept in this framework is to reflect with a self-critical lens. Be honest with yourself to determine if you have a basic talent and if will you have the commitment to nurture it. The next step is building out the path to facilitate your passion.

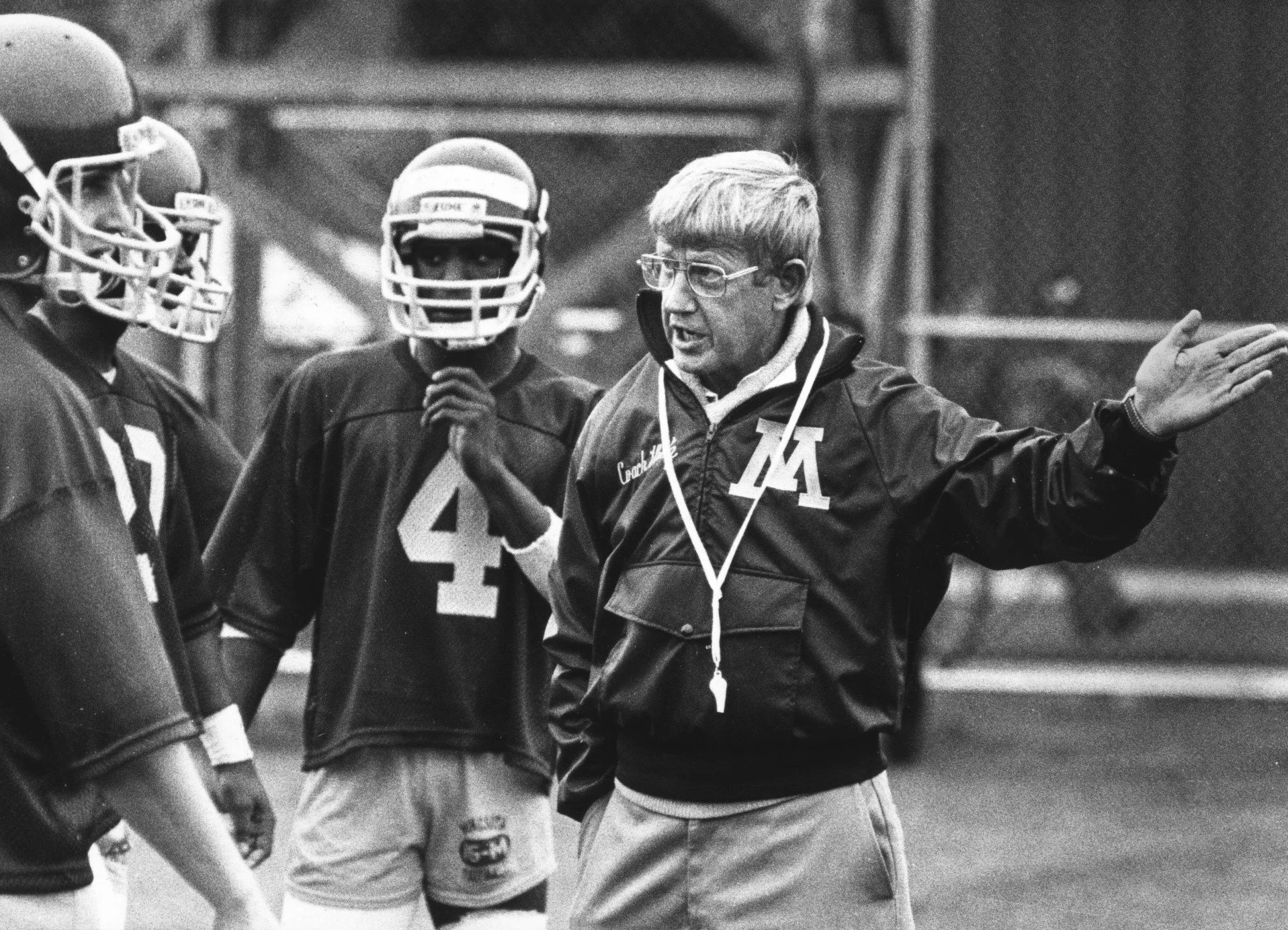

“Ability is what you’re capable of doing. Motivation determines what you do. Attitude determines how well you do it.”

—Lou Holtz

How do you get into the driver’s seat?

Concept Three: map out the path that will allow you to be a key decision maker (or key individual contributor). Finding and nurturing a passion is primarily an internal endeavor that is a foundational building block to a career. Determining the application and interaction with external forces is what animates a passion.

You will need to find the opportunity to be able to apply your skills in your passion. More specifically, the opportunity must allow you to be the driver of a business or at least a key contributor of the driving function of a business. This does not mean you have to be the CEO of a firm, but it does mean that you (or your group) guides the business. The reason for this is because being in the frontline of decision making activates the core skill of your passion, thereby allowing you to further refine, learn, and grow.

I will use a personal anecdote to illustrate this concept. My two job opportunities after school were either 1) working at an investment bank in investment management or 2) working at a car company in a finance leadership rotation program. I had always had an interest in financial markets and thought that would be my path since I was 10 years old. However, cars had a much stronger pull for me. I had just thought that cars would be a hobby because I had never considered a path to make cars into a career.

I took a step back and started thinking about the opportunity to jump into the industry that I had loved for forever. Though it was in the group that was as far away as possible from the actual brand strategy and product ideation, I began thinking if there was a realistic map to allow me to join the core decision-making department of car making (in my ex-firm’s case, product marketing & planning). Thus, I signed on the dotted line and was a finance guy in the car business. Four weeks later (after some negotiations and turns), I found myself a new role in one of our brand’s product marketing & planning group, and then for the next five years, I helped create the product portfolio and brand strategies for two historic Italian brands.

This does not mean to say that ancillary groups are automatically stricken off a list when hunting for the next opportunity. Rather, understanding if that group is a key input or support to a firm’s overall strategy is equally as important as the driving department of that firm. For example, if a software firm is hyper-customer centric, you will need a strong user experience research group to bridge the gap between customer needs and the driving function of the engineers in order to refine and improve the core product. Therefore, if your passion is psychology and user experience, user experience research could be the right role for you in such instance.

Building a roadmap to becoming a key decision maker is critical so that you can execute your developed skills of your chosen passion. The execution is equally as important as the preparation in order to animate your passion so that you can continue to grow and learn.

“Some people are pragmatists, taking things as they come and making the best of the choices available. Some people are idealists, standing for principle and refusing to compromise. And some people just act on any whim that enters their heads. I pragmatically turn my whims into principles!”

—Calvin from Calvin & Hobbes

Conclusion

If you adhere to this rational framework to embark on an emotional pursuit, you can ensure long term success in following what you love doing. To summarize:

Identify the field or function that you love

Be honest to see if you have the base skills and then the willingness to cultivate these skills in what you love

Strategize a path to applying your skills as a key decision maker and driver

This is the best way to spend the majority of your waking life. The moment you stop learning and get complacent is the time you know it is time to start looking for your next adventure.